biocircuit analysis by binding and catalysis (ABC)

log derivatives have strong structures in biocircuits, and dynamic properties can be encoded in them, such as stability, control, multistability, and oscillations, in an intuitive way.

See here for a relevant 12-min video introduction and this paper and this paper for some details. Part of this work was done during my visit to Mustafa Khammash group at ETH in summer 2019.

Log derivatives have strong structures in biocircuits. Dynamical properties and system functions can thus be analyzed and designed from log derivatives of a biocircuit. Also, because of the holistic nature of the log derivative view, artifacts from assumptions in models such as retroactivity simply disappear, and the recent generation of biocircuits with highly varying molecule concentrations, e.g. in post-translational regulations or from developmental biology, are naturally accomodated. I illustrate this via a few examples below.

Adaptation in biocircuits and how they fail

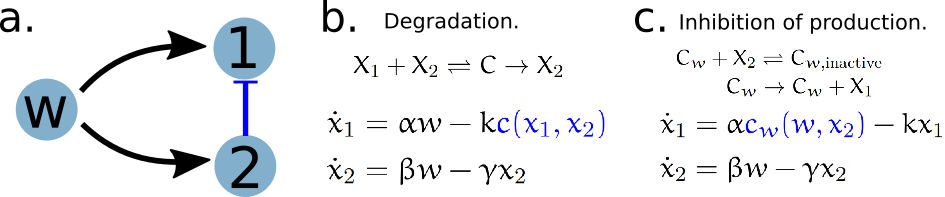

Let us consider the incoherent feed-forward loop (IFFL) motif in systems biology that is widely regarded as an architecture used in gene regulatory networks to achieve adaptation to environmental disturbances. A simlpe IFFL motif is of the following form (panel a).

The control objective is to make \(x_1\), the concentration of \(X_1\) molecule, robust to changes in the concentration \(w\) of disturbance molecule \(W\). Because \(W\) activates \(X_1\), this IFFL motif uses a negative regulation arm through \(X_2\) that cancels the activation arm. Specifically, the negative regulation arm has \(W\) activating \(X_2\), which in turn inhibits \(X_1\).

There are multiple implementations of this IFFL motif through molecular reactions. We compare two such implementations that differ in how \(X_2\) inhibits of \(X_1\). Panel (b) describes a degradation implementation, where the inhibition acts via \(X_2\) catalyzing the degradation of \(X_1\). Panel (c) describes a repressive binding implementation, where the inhibition acts via \(X_2\) inhibiting the production of \(X_1\) by \(W\). The active complex for the degradation implementation is \(C\) formed by the binding of \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), while the active complex for the repression implementation is \(C_W\) that could be sequestered by \(X_2\) to form inactive complex \(C_{w,\mathrm{inactive}}\).

The regulatory profiles of the key catalysis reactions, i.e. degradation and production, are then characterized by the log derivative polyhedra of the \(C\) and \(C_w\) complexes respectively. We can then understand when and how the circuit adapts to disturbances by looking at how the system state moves in the log derivative polyhedra.

Let us first look at the degradation implementation under perturbations.

As time goes on, we apply disturbances \(w\) that first decrease, then increase with larger and larger magnitude. We see that \(x_1\) does not change much, i.e. adapts, for decreasing \(w\) or small increasing \(w\). But for large increasing \(w\), \(x_1\) is significantly disturbed. This can be mechanistically understood by looking at the log derivative polyhedra of \(C\). When \(w\) is decreasing or when \(w\) has a small increase, the log derivatives of \(C\) stays in the corner near \((1,1)\) (red in figure), which is the adaptive regime. When \(w\) has a large increase, we see log derivatives of \(C\) is driven out of that corner, therefore the circuit loses its adaptibility.

We can use the same method to inspect the repression implementation of IFFL.

We see at the beginning, for increasing \(w\) or small decreasing \(w\), \(x_1\) adapts. Correspondingly, the log derivatives of \(C_w\) stays near the red stripe, the adaptive regime. Later on, for \(w\) with large decreases, \(x_1\) fails to adapt, corresponding to log derivatives of \(C_w\) driven out of the red stripe.

From this inspection, we see that the two implementations of IFFL have the function adapting \(x_1\) to disturbances in \(w\), but they fail in different ways. While the degradation implementation fails for \(w\) with large increases, the repression implementation fails for \(w\) with large decreases. This difference is fundamentally rooted in the different geometry of their adaptive regimes in their respective log derivative polyhedra. This shows that the holistic system view not only allows the theoretical analysis for a model describing a properly functioning biocircuit, but also enables debugging for when and how a biocircuit might fail. This debugging or failure-catching capability is essential for building up computer-aided design methods of biocircuits that can reliably perform in reality.