flux exponent control (FEC) for dynamic metabolism

modelling metabolism dynamics through constraint-based approach that can utilize sparse data; upgrade flux balance analysis (FBA) to naturally accomodate dynamics; FEC includes biological constraint that cells regulat metabolism via binding reactions.

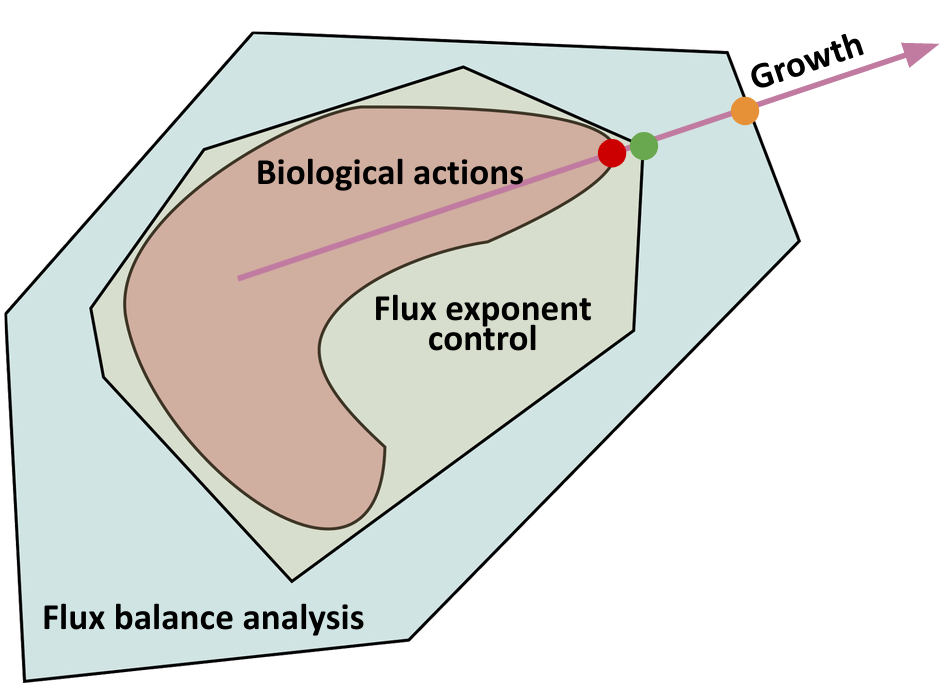

Metabolism dynamics is fundamentally hard to describe using the traditional specific-model approach, where explicit equations are written down with many parameters to be identified through experiments. The complication is that while we can experimentally measure bulk metabolic fluxes at scale and characterize metabolite stoichiometry robustly, we lack systematic ways to observe the dynamic fluxes of intermediates in cells which depend on the concentrations of regulatory proteins. In order to resolve this complication, a constraint-based approach has been developed to model metabolism. The constraint-based approach dominated recent progress on computational models of large scale metabolic networks. Constraint-based methods consider the metabolic flux regulation as a solution to an optimization problem, where our “hard” knowledge about the systems from accurate but sparse data, such as stoichiometry, is supplied as constraints on the metabolic fluxes. A constraint-based method will yield the true biological solution if the constraints and objectives are exactly correct (see figure below). Since objectives can vary in computation to scan for plausible behaviors, finding a good model then shifts from finding the right functional forms and parameters in the specific-model approach to finding the right constraints in constraint-based approach.

The simplest constraint-based approach, dynamic flux balance analysis (dFBA), uses only the stoichiometry of metabolic network as constraint (see figure blow). It also assumes that metabolism is fast and reaches steady state (i.e. the fluxes balance to a certain value), so that the optimization problem is easily solvable (static instead of dynamic), albeit restricted to timescales slower than metabolism. Since its proposal, dFBA has enjoyed multiple successes in modeling large scale metabolic networks. In particular, recent work illustrates that dFBA could capture complex behaviors of a microbial consortia such as hysteresis and bistability that is hypothesized to underlie the switching between beneficial and detrimental gut microbiome compositions.

Although it holds promise as a constraint-based approach to study metabolism, dFBA has severe limitations in applying to metabolism dynamics of interacting cells and populations. dFBA cannot model dynamics of metabolic regulations as it assumes the intracellular metabolic fluxes are always at steady state. In comparison, many significant metabolic dynamics in the gut microbiome, for example, happens within minutes to hours. In addition, as the strength of a constraint-based method comes from the set of constraints it could use, dFBA only incorporates the stoichiometry of metabolic reactions as a constraint, so it could be considered as overly unconstrained to include un-biological actions such as instantaneous changes of metabolic flux (see figure below). This causes predictions of dFBA to be erroneous without time-consuming hand-tuning and curating by experts on the microbe modeled.

Using our foundational understanding of bioregulation as binding and catalysis, we obtain a fundamental constraint for metabolism dynamics that can be used to improve constraint-based modelling. Namely, that since cells regulate metabolic fluxes (which are catalysis reactions) via binding reactions, the regulatory profiles of metabolic fluxes are characterized by polyhedral constraints on the reaction orders (or exponents or log derivatives). As metabolites’ concentrations vary, the fluxes are regulated by changing the reaction orders inside their respective polyhedra. We can incorporate this knowledge as a fundamental constraint on metabolic regulation, that metabolic control actions are done on fluxes’ reaction orders (i.e. exponents). We call the constraint-based method incorporating this constraint flux exponent control (FEC). With FEC, we can further constrain all possible regulations of metabolic fluxes and formulate constraint-based models without steady state assumptions in dFBA to capture the dynamics of metabolism. Since FEC restricts ways that reaction fluxes can be regulated further than just stoichiometry in dFBA, it has stricter yet biological constraints so that our prediction is closer to truth (see figure above).

FEC also has the advantage of allowing for more complex objectives beyond optimizing for growth that is more appropriate for biology outside laboratories. For example, survival without growth is more appropriate for microbes in most natural environments (nicely reviewed here). While FBA-based methods are restricted to optimizing for some metabolites’ steady state output, FEC can be posed as optimal controllers for any (dynamic) objective, including maintaining a healthy steady state for survival without growth. This makes FEC uniquely capable as a constraint-based method that captures microbial metabolism dynamics in diverse environments.

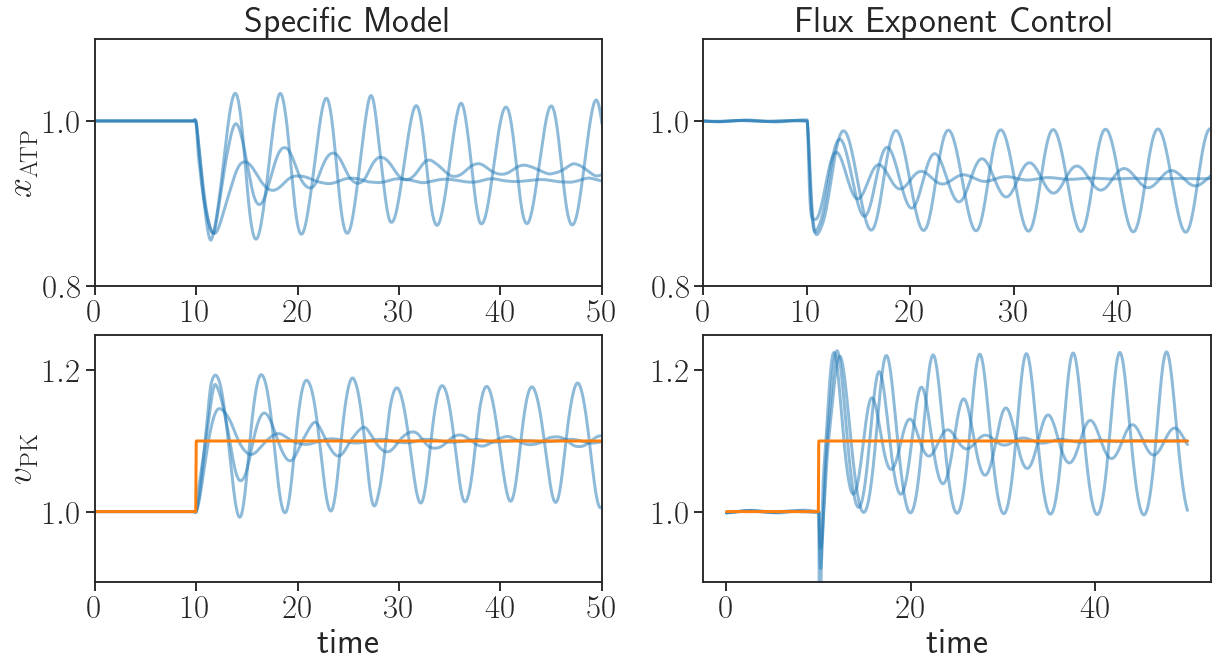

We illustrate the power of FEC to capture metabolism dynamics with glycolytic osillations. Glycolytic oscillations, where metabolite concentrations (e.g. ATP) oscillate in the glycolysis pathway, has been widely observed and studied from yeast to human muscle since 1960s both theoretically and experimentally. Although detailed models were constructed to show that feedbacks of autocatalysis and allosteric control of ATP on PFK were necessary and sufficient for glycolytic oscillation, the deeper “why” questions and the full generality of this type of behavior were unanswered until this work showed in 2011 that oscillations are necessary side effects of robustness and efficiency tradeoffs. Specifically, it was shown that by combining a law on conservation of robustness in systems theory called Bode’s integral formula with the autocatalytic stoichiometry of glycolysis, a universal rule of metabolic regulation can be obtained that includes glycolytic oscillation as a subset: Any regulatory circuit that must robustly maintain metabolite concentrations despite fluctuations in supply and demand will inevitably have significant oscillations. Below we show that FEC can capture glycolytic oscillation with only knowledge about the autocatalytic stoichiometry of glycolysis, recovering the principle above.

FEC Captures Glycolytic Oscillation. FEC enables dynamic predictions of metabolic behavior by solving for flux regulations as optimal controllers acting on the exponents. This allows actual predictions of metabolism dynamics using only the stoichiometry of the metabolic network. Principles of metabolic control therefore can be explored via FEC.

The autocatalytic stoichiometry of glycolysis could be captured in a simple metabolic network with two metabolites, following the 2011 work. Note that this aims to capture the autocatalytic structure of glycolysis, while details such as the exact numbers of molecules involved are not essential. \begin{equation} \label{eqn:glycolysis} X_{\text{ATP}} \xrightarrow{k_{\text{PFK}} C_{\text{PFK}}} X_{\text{6Cp}}, \hspace{2mm} X_{\text{6Cp}} \xrightarrow{k_{\text{PK}} C_{\text{PK}}} 2 X_{\text{ATP}}, \hspace{2mm} X_{\text{ATP}} \xrightarrow{\delta} \emptyset. \end{equation} The reactions in \eqref{eqn:glycolysis} are the following. Assuming a supply of sugars, ATP is first consumed to produce a pool of intermediate metabolites \(X_{\text{6Cp}}\), such as phosphorylated six-carbon sugars. This reaction has reaction rate constant \(k_{\text{PFK}}\) which defines the unregulated steady state flux and has flux proportional to the concentration of phosphofructokinase (PFK) or PFK-like enzymes, as represented by \(C_{\text{PFK}}\). The intermediates are then consumed in another reaction to produce more ATP, which has rate constant \(k_{\text{PK}}\) and is catalyzed by pyruvate kinase (PK) or PK-like enzymes, as represented by \(C_{\text{PK}}\). Lastly, ATP is also consumed for general maintenance of the cell, with flux \(\delta\). When the cell is disturbed, e.g. under heat shock, then \(\delta\) increases since higher maintenance cost is needed then. We emphasize that the rate constants here are unregulated steady state fluxes, which only need to be roughly specified in orders of magnitude to capture any important dynamical features using FEC. Rough estimates can come from simple ball-parking or preliminary FEC simulations without any experiments. On the other hand, any more detailed specifications on the rate constants or the regulation of the metabolism network can be easily incorporated in FEC to enhance the quantitative predictions. In contrast, specific models such as the one introduced in the 2011 work and plotted in the left panel of the following figure make specific assumptions about the flux regulatory circuit, i.e. how concentrations of the flux intermediates \(c_{\mathrm{PFK}}\) and \(c_{\mathrm{PK}}\) depend on metabolite concentrations \(x_{\mathrm{ATP}}\) and \(x_{\mathrm{6CP}}\). Such assumptions and the parameters used in them are fundamentally hard to validate experimentally as these are dynamics of reactions fluxes inside cells. FEC formulation keeps flux regulatory circuits, and explore them as optimal regulatory strategies for various objectives.

By specifying the control objective as keeping intermediates and ATP levels close to their steady-state values to adapt under disturbances, we solve for \(c_{\mathrm{PFK}}\) and \(c_{\mathrm{PK}}\) as optimal controllers of flux exponents in FEC. This generates the right-panel trajectories in the above figure. We see that the oscillatory behavior is captured by FEC where the only data used is the stoichiometry of the metabolic network. In contrast, FBA (orange), due to its steady state assumption, predicts a flat line, failing to capture the oscillatory behavior, while the specific model (blue left panel) required assumptions of specific forms of flux regulation, which is feasible with biologically plausible predictions in this case only because of more than six decades of experimental and theoretical research on this simple system. We emphasize that the glycolytic oscillation is explored here via FEC with no assumption other than the stoichiometry, therefore we can reach general rules about this phenomena, like in the 2011 work but in a systematic way. This does not rely on relevant control theoretical principles to be already known, but instead can be used to suggest and discover control principles.